meta data for this page

1.A.4.a ii - Commercial / Institutional: Mobile

Short description

In NFR 1.A.4.a ii - Commercial/institutional: Mobile fuel combustion activities and emissions from non-road diesel and LPG-driven (forklifters) vehicles used in the commercial and institutional sector are taken into account.

| Method | AD | EF | Key Category Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1, T2 | NS, M | CS, D, M | no key category |

Methodology

Activity data

Sector-specific diesel consumption data are included in the primary fuel-delivery data available from NEB line 67: 'Commercial, trade, services and other consumers' (AGEB, 2021) 1).

Table 1: Sources for primary fuel-deliveries data

| through 1994 | NEB line 79: 'Households and small consumers' | ||

| as of 1995 | NEB line 67: 'Commercial, trade, services and other consumers' |

Following the deduction of diesel oil inputs for military vehicles as provided in (BAFA, 2021) 2), the remaining amounts of diesel oil are apportioned onto off-road construction vehicles (NFR 1.A.2.g vii) and off-road vehicles in commercial/institutional use (1.A.4.a ii) as well as agriculture and forestry (1.A.4.c ii) based upon annual shares derived from (Knörr et al. (2021b)) 3) (cf. superordinate chapter).

Table 2: Annual contribution of NFR 1.A.4.a ii to the over-all amounts of diesel oil provided in NEB line 67

| 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.01% | 6.65% | 6.99% | 7.18% | 6.86% | 6.80% | 6.59% | 6.52% | 6.52% | 6.36% | 6.21% | 5.96% | 5.82% | 5.73% | 5.83% | 5.78% | 5.68% | 5.59% | 5.45% |

source: TREMOD MM 4)

As the NEB does not distinguish into specific biofuels, consumption data for biodiesel are calculated by applying Germany's official annual shares of biodiesel blended to fossil diesel oil.

In contrast, for LPG-driven forklifters, specific consumption data is modelled in TREMOD-MM. These amounts are then subtracted from the over-all amount available from NEB line 67 to estimate the amount of LPG used in stationary combustion.

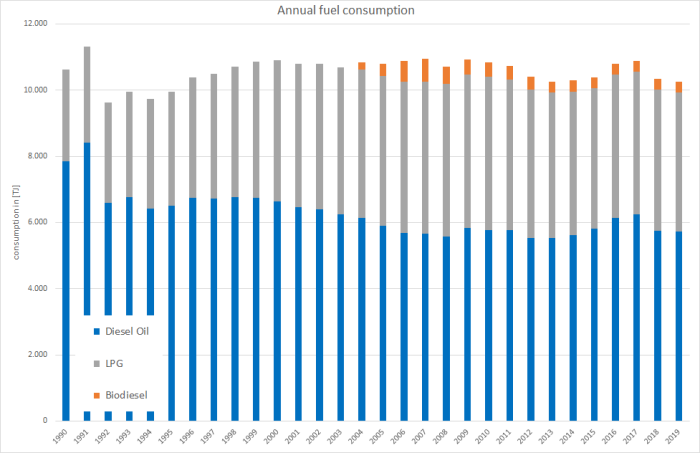

Table 3: Annual fuel consumption, in terajoules

| 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel Oil | 7,847 | 6,508 | 6,646 | 5,894 | 5,691 | 5,658 | 5,583 | 5,842 | 5,773 | 5,770 | 5,533 | 5,524 | 5,629 | 5,810 | 6,145 | 6,257 | 5,749 | 5,736 | 5,694 |

| Biodiesel | NO | NO | NO | 377 | 629 | 696 | 530 | 467 | 443 | 403 | 390 | 328 | 346 | 318 | 326 | 334 | 334 | 327 | 473 |

| LPG | 2,787 | 3,450 | 4,261 | 4,533 | 4,563 | 4,587 | 4,606 | 4,620 | 4,629 | 4,557 | 4,484 | 4,409 | 4,333 | 4,256 | 4,336 | 4,301 | 4,264 | 4,213 | 4,139 |

| Ʃ 1.A.4.a ii | 10,634 | 9,958 | 10,907 | 10,803 | 10,883 | 10,942 | 10,719 | 10,929 | 10,844 | 10,729 | 10,407 | 10,261 | 10,307 | 10,383 | 10,807 | 10,892 | 10,346 | 10,276 | 10,306 |

Emission factors

The emission factors used here are of rather different quality: Basically, for all main pollutants, carbon monoxide and particulate matter, annual IEF modelled within TREMOD MM are used, representing the sector's vehicle-fleet composition, the development of mitigation technologies and the effect of fuel-quality legislation.

As no such specific EF are available for biofuels, the values used for diesel oil are applied to biodiesel, too.

Table 4: Annual country-specific emission factors from TREMOD MM, in kg/TJ

| 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel fuels1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| NH3 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| NMVOC | 247 | 223 | 197 | 139 | 128 | 118 | 109 | 101 | 93.0 | 85.7 | 78.6 | 71.4 | 64.6 | 58.6 | 53.8 | 50.0 | 46.9 | 44.2 | 41.6 |

| NOx | 1,000 | 1,026 | 1,004 | 833 | 794 | 755 | 714 | 673 | 633 | 595 | 560 | 528 | 501 | 477 | 453 | 431 | 410 | 392 | 373 |

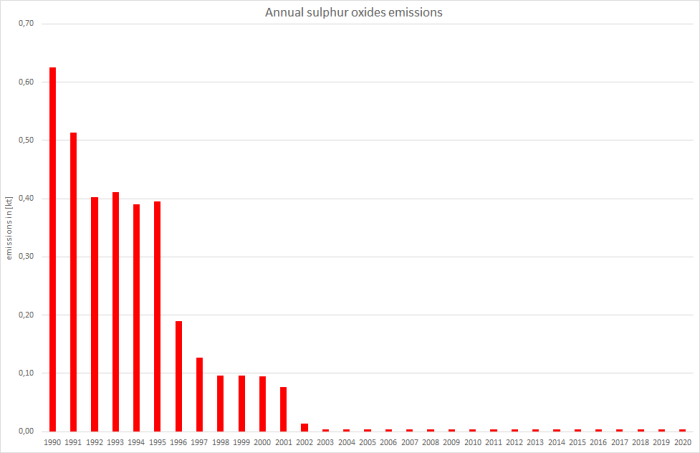

| SOx | 79.6 | 60.5 | 14.0 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| BC3 | 107 | 88.7 | 74.4 | 55.3 | 51.7 | 48.6 | 46.2 | 44.1 | 42.2 | 40.5 | 38.7 | 36.6 | 34.3 | 32.1 | 30.0 | 28.3 | 26.8 | 25.4 | 23.9 |

| PM2 | 194 | 161 | 134 | 93.6 | 86.0 | 79.4 | 73.8 | 69.0 | 64.4 | 60.1 | 56.0 | 51.6 | 47.1 | 43.0 | 39.5 | 36.7 | 34.5 | 32.5 | 30.5 |

| CO | 856 | 796 | 725 | 560 | 530 | 502 | 476 | 451 | 429 | 407 | 387 | 368 | 351 | 338 | 329 | 322 | 318 | 313 | 307 |

| LPG | |||||||||||||||||||

| NH3 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| NMVOC | 148 | 147 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 144 | 141 |

| NOx | 1,346 | 1,342 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,325 | 1,316 | 1,284 |

| SOx | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| BC3 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| PM2 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| CO | 114 | 114 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 | 112 |

1 due to lack of better information: similar EF are applied for fossil and biofuels

2 EF(PM2.5) also applied for PM10 and TSP (assumption: > 99% of TSP consists of PM2.5)

3 estimated via a f-BCs as provided in 5), Chapter 1.A.2.g vii, 1.A.4.a ii, b ii, c ii, 1.A.5.b i - Non-road, note to Table 3-1: Tier 1 emission factors for off-road machinery

With respect to the emission factors applied for particulate matter, given the circumstances during test-bench measurements, condensables are most likely included at least partly. 1)

For information on the emission factors for heavy-metal and POP exhaust emissions, please refer to Appendix 2.3 - Heavy Metal (HM) exhaust emissions from mobile sources and Appendix 2.4 - Persistent Organic Pollutant (POP) exhaust emissions from mobile sources. - Here, for lead (Pb) from leaded gasoline and corresponding TSP emissions, additional emissions have been calculated from 1990 to 1997 based upon contry-specific emission factors from TREMOD MM.

Discussion of emission trends

NFR 1.A.4.a ii is no key source.

Unregulated pollutants

For all unregulated pollutants, emission trends directly follow the trend in fuel consumption.

Regulated pollutants

Nitrogen oxides and Sulphur dioxide

For all regulated pollutants, emission trends follow not only the trend in fuel consumption but also reflect the impact of fuel-quality and exhaust-emission legislation.

Particulate matter & Black carbon

Over-all PM emissions are by far dominated by emissions from diesel oil combustion with the falling trend basically following the decline in fuel consumption between 2000 and 2005. Nonetheless, the decrease of the over-all emission trend was and still is amplified by the expanding use of particle filters especially to eliminate soot emissions.

Additional contributors such as the impact of TSP emissions from the use of leaded gasoline (until 1997) have no significant effect onto over-all emission estimates.

Here, as the EF(BC) are estimated via fractions provided in the 2019 EMEP Guidebook 6), black carbon emissions follow the corresponding emissions of PM2.5.

Recalculations

Activity data hase been revised according to the now finalized National Energy Balance 2019.

Table 5: Revised activity data 2019, in terajoules

| DIESEL OIL | BIODIESEL | LPG | OVER-ALL FUEL CONSUMPTION | |

| current submission | 5.736 | 327 | 4.213 | 10.276 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| prvious submission | 5.726 | 326 | 4.213 | 10.266 |

| absolute change | 10,2 | 0,69 | 0,00 | 10,9 |

| relative change | 0,18% | 0,21% | 0,00% | 0,11% |

For pollutant-specific information on recalculated emission estimates for Base Year and 2019, please see the recalculation tables following chapter 8.1 - Recalculations.

Uncertainties

Uncertainty estimates for activity data of mobile sources derive from research project FKZ 360 16 023: “Ermittlung der Unsicherheiten der mit den Modellen TREMOD und TREMOD-MM berechneten Luftschadstoffemissionen des landgebundenen Verkehrs in Deutschland” by (Knörr et al. (2009)) 7).

Uncertainty estimates for emission factors were compiled during the PAREST research project. Here, the final report has not yet been published.

Planned improvements

Besides the annual routine revision of TREMOD MM, no specific improvements are planned.

FAQs

Why are similar EF applied for estimating exhaust heavy metal emissions from both fossil and biofuels?

The EF provided in 8) represent summatory values for (i) the fuel's and (ii) the lubricant's heavy-metal content as well as (iii) engine wear. Here, there might be no heavy metal contained in biofuels. But since the specific shares of (i), (ii) and (iii) cannot be separated, and since the contributions of lubricant and engine wear might be dominant, the same emission factors are applied to biodiesel and bioethanol.